Common Conditions and Treatments for Stomach, Digestive, Liver, and Nutrition Disorders

Conditions

- Abdominal pain

- Biliary atresia

- Celiac disease

- Colic

- Constipation

- Encopresis

- Diarrhea (Acute and chronic)

- Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)

- Failure to Thrive (FTT)

- Hepatitis (A, B, C, and autoimmune)

- Hirschsprung disease

- Inflammatory bowel disease (Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease)

- Nutrition and obesity

- Pancreatitis

- Reflux and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Treatments

- Achalasia pneumatic dilation

- Anorectal manometry

- Breath hydrogen testing

- Colonoscopy

- Endoscopic treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding

- Esophageal dilation

- Esophageal manometry

- Esophageal varices banding

- Esophageal varices sclerotherapy

- Flex sigmoidoscopy

- Foreign body removal

- Pancreatic function testing

- Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement and care

- pH probe/impedance

- Polypectomy

- Pyloric dilation (including Botox injections)

- Rectal dilation (including Botox injections)

- Rectal suction biopsy

- Single balloon enteroscopy

- Upper endoscopy

- Video capsule endoscopy

Most otherwise-healthy children who repeatedly complain of stomachaches for two months or more have functional abdominal pain. The term “functional” refers to the fact that there is no blockage, inflammation or infection causing the discomfort. Your GI Provider will help determine whether your child’s pain is functional. Nevertheless, the pain is very real, and is due to extra sensitivity of the digestive organs, sometimes combined with changes in gastrointestinal movement patterns. A child’s intestine has a complicated system of nerves and muscles that helps move food forward and carry out digestion. In some children, the nerves become very sensitive, and pain is experienced even during normal intestinal functions. The pain can be triggered by illness, stress, constipation, or other factors. These children often miss school and activities. Fortunately, despite recurrent pain, these children have normal growth and are generally healthy.

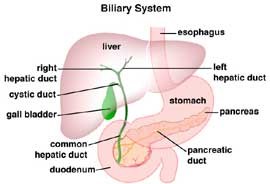

Biliary atresia is a rare disease of the liver and bile ducts that occurs in infants. Symptoms of the disease appear or develop about two to eight weeks after birth. Cells within the liver produce liquid called bile. Bile helps to digest fat. It also carries waste products from the liver to the intestines for excretion.

This network of channels and ducts is called the biliary system. When the biliary system is working the way it should, it lets the bile drain from the liver into the intestines.

When a baby has biliary atresia, bile flow from the liver to the gallbladder is blocked. This causes the bile to be trapped inside the liver, quickly causing damage and scarring of the liver cells (cirrhosis), and eventually liver failure.

The causes of biliary atresia are not completely understood. For some children, biliary atresia may occur because the bile ducts did not form properly during pregnancy. For other children with biliary atresia, the bile ducts may be damaged by the body's immune system in response to a viral infection acquired after birth.

Babies with biliary atresia usually appear healthy when they are born. Symptoms of the disease typically appear within the first two weeks to two months of life. Symptoms include: jaundice, dark urine, clay-colored stools, weight loss or irritability. Biliary atresia is diagnosed through blood tests, xrays to look for an enlarged liver, and liver biopsy. Diagnostic surgery with operative cholangiogram confirms diagnosis.

Biliary atresia cannot be treated with medication. A Kasai procedure or hepatoportoenterostomy is done. The Kasai procedure is an operation to re-establish bile flow from the liver into the intestine. It is named after the surgeon who developed it. The surgeon removes the damaged ducts outside of the liver (extrahepatic ducts) and identifies smaller ducts that are still open and draining bile. The surgeon then attaches a loop of intestine to this portion of the liver, so that bile can flow directly from the remaining healthy bile ducts into the intestine. With an experienced surgeon, the Kasai procedure is successful in 60 to 85 percent of the patients. This means that bile drains from the liver and the jaundice level goes down. The Kasai procedure is not a cure for biliary atresia, but it does allow babies to grow and have fairly good health for several, sometimes for many, years. In 15-40 percent of patients the Kasai procedure does not work. If this is the case, liver transplantation can correct this problem.

Nearly half of all infants who have had a Kasai procedure require liver transplantation before age 5. Older children may continue to have good bile drainage and no jaundice.

Eighty-five percent of all children who have biliary atresia will need to have a liver transplant before they are 20 years old. The remaining 15 percent have some degree of liver disease. Their disease can be managed without having a transplant.

Celiac disease is a genetic autoimmune disorder that affects both children and adult. If a child has celiac disease, consuming gluten will cause damage to finger-like projections, called villi, in the lining of the child's small intestines. This, in turn, interferes with the small intestine’s ability to absorb nutrients in food, leading to malnutrition and a variety of other complications. The protein in wheat, barley, rye and oats collectively called “gluten” cause the immune system to form antibodies which then attack the villi. If the villi are damaged, the child cannot absorb nutrients. These children with Celiac disease may suffer from symptoms such as abdominal bloating, pain, gas, diarrhea, constipation, weight loss, anemia, growth problems, and short stature.

Celiac disease is a life-long condition, but it is manageable through permanent changes to the diet called a gluten free diet which is a healthy diet that includes fruits and vegetables, eggs, meat, poultry--and even soft drinks and ice cream!

Colic is a common condition in babies causing inconsolable crying and extreme fussiness, particularly in the evening. It is thought to be a self-limited behavioral syndrome. Typically colic starts by 3 weeks of age, lasts at least 3 hours a day, and occurs at least 3 days a week. These babies cry as if they are in pain, turning red and arching their back.

Colic is very common. Nearly 1 in 4 newborns are affected. Colic is thought to occur because of the immaturity of the baby’s nervous system, sleeping disruption, hypersensitivity to the environment and sensory overload. Only a small fraction of the children with colic will actually be suffering from medical conditions. There is no treatment, but much can be done to minimize the impact on the parents of this exhausting problem. The baby’s formula may be changed to one that is hypoallergenic. Some breastfeeding mothers will modify their own diet, removing gas-producing foods or dairy products. The most effective treatment is time and patience. Other family members can take turns with the baby’s care. Infant massage, soothing music, and swaddling can help soothe a colicky baby. Colic will usually resolve by the time the baby is three months old. Sometimes, the fussiness lasts for a few more weeks or months.

Constipation is defined as either a decrease in the frequency of bowel movements or the painful passage of bowel movements. Most children should have a bowel movement 1 – 2 times a day but many children go at least every other day. When children are constipated for a long time, they may begin to soil their underwear. This fecal soiling is involuntary, and the child has no control over it. Constipation affects children of all ages.

Constipation is often defined as being organic or functional. Organic means there is an identifiable cause such as colon disease or a neurological problem. Fortunately, most constipation is functional meaning there is no identifiable cause. The constipation is still a problem, but there is usually no worrisome cause behind it.

In some infants, straining and difficulties in expelling a bowel movement (often a soft one) are due to their immature nervous system and uncoordinated defecation. Also, it should be remembered that some healthy breast-fed infants can skip several days without having a movement.

In children, constipation can begin when there are changes in the diet or routine, during toilet training, or after an illness. Some children hold stools because they do not want to use public rest rooms or do not want to stop what they are doing. Once the child has been constipated for more than a few days, the retained stool can fill up the large intestine (the colon) and cause it to stretch. An over-stretched colon cannot work properly, and more stool is retained. Defecation becomes very painful and many children will attempt to withhold stool because of the pain. Withholding behaviors include tensing up, crossing the legs or tightening up leg/buttock muscles when the urge to have a bowel movement is felt. Many times these withholding behaviors are misinterpreted as attempts to push the stool out. Stool withholding will make constipation worse and treatment more challenging.

Treatment consists of laxatives, dietary modifications, increasing fluids, and behavior training. It may take 1 year or more to treat constipation.

When constipation is not controlled, fecal soiling may occur. Encopresis occurs when the child’s colon is impacted with hard stool and the soft or liquid stool can leak out of the anus and stains the child’s underwear. Usually this is caused by chronic constipation. Less frequently, it may be a result of developmental or emotional stress. The soiling can cause significant disruption and embarrassment to the child who usually has lost the sensation to feel stool leaking out. Encopresis can lead to a struggle within the family and cause significant emotional and psychological difficulties and can manifest with problems at school, low self-esteem, and peer conflicts.

As with constipation, the treatment consists of laxatives, dietary modifications, increasing fluids, and behavior training. Children who have had emotional and psychological difficulties may benefit from psychological counseling. It usually takes more than a year to treat encopresis.

Diarrhea, an increase in the number of stools per day and/or an increase in their looseness, is a common problem that generally lasts only a few days. Diarrhea that has lasted for less than one week is considered to be “acute”. The most common causes of acute diarrhea include viruses, bacteria and parasites, food poisoning, medications especially antibiotics, food allergies, and toxic substances. Acute diarrhea stops when the body clears the provoking infection or toxin. Most viruses and bacteria do not require treatment with antibiotics. If the diarrhea persists for longer than one or two weeks, stool and blood tests will help determine the most likely cause of the problem and guide treatment. Children with acute diarrhea should continue to eat their regular diet, unless the diarrhea is severe or accompanied by vomiting. Sometimes, restriction of milk and dairy products might be helpful, but is not necessary. Excessive fluid loss can result in dehydration which can be avoided by making sure the child is drinking enough fluids to maintain normal urine output. Infants under 3 months of age and those who are vomiting are at the highest risk for dehydration. High fever increases the body fluid losses and should therefore be controlled. A decrease in the number of wet diapers, lack of tears when crying, and excessive sleepiness are all signs of dehydration and require medical attention. When the diarrhea is severe or there is vomiting, replacement fluid mineral drinks such as Pedialyte, Infalyte, Cerealyte, Naturalyte and Rehydralyte are recommended. These are also available in popsicles. If the child cannot keep enough fluid in, hospitalization is recommended to prevent serious dehydration and to allow “bowel rest” while the infection runs its course. Feedings by mouth will be started as soon as the condition improves and while the child’s response can be watched more closely.

Diarrhea is an increase in the number of stools per day and/or more loose or liquid stools. When diarrhea lasts for more than four weeks, it is called “chronic”. There are many causes of chronic diarrhea. Some exist in healthy people, but others are diseases that need long term medical care.

These are some of the causes:

- Infections with bacteria or parasites

- Irritable bowel syndrome, which is due to more rapid colon action

- Toddler’s diarrhea, which is also from more rapid colon action and is often worsened by excessive sugars such as from drinking juice

- Milk and soy allergies in infants

- Leakage of loose stool around constipated stool that is stuck in the rectum

- Intolerance of lactose (from milk) or fructose (from fruit juice)

- Inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

- Celiac disease, which is damage to the small intestine from wheat protein

Your GI provider will do a thorough exam and may order tests to determine the cause of chronic diarrhea and provide treatment.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE)

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an inflammatory condition in which the wall of the esophagus becomes filled with large numbers of white blood cells called eosinophils. Because this condition inflames the esophagus, someone with EoE may experience difficulty swallowing, pain, nausea, regurgitation, and vomiting. Over time, the disease can cause the esophagus to narrow, which sometimes results in food becoming stuck, or impacted, within the esophagus, requiring emergency removal.

In young children, many of the symptoms of eosinophilic esophagitis resemble those of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)—including feeding disorders and poor weight gain—so the child may be mistakenly diagnosed with GERD. However, proper diagnosis of esophagitis in children is important because it is a serious disease that can cause lifelong problems if undiagnosed.

Failure to thrive (FTT) is a phrase that is used to describe children who have fallen short of their expected growth and development. FTT occurs when your child is either not receiving adequate calories or is unable to properly use the calories that are given, resulting in failure to grow or gain weight over a period of time. Using standard growth charts, achild’s weight or height below the 3rd percentile for age or a progressive decrease in the rate of gain of weight or height would be considered as FTT.

Failure to thrive happens for many reasons, but the causes can be divided into three categories: poor intake, poor utilization, or increased calorie requirements. Among the conditions that can cause your child to have inadequate calories for normal growth (decreased intake of calories) include: refusal to eat caused by medical problems such as gastroeophageal reflux, having a restrictive diet, poor milk supply in breastfeeding moms, physical abnormalities causing difficulty swallowing, poverty. Conditions that can cause an increased loss of calories include illnesses that cause vomiting, malabsorption from conditions such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, food allergies and parasites. Other children may have an increased requirement for calories because of a chronic infection, hyperthyroidism, congenital heart disease or chronic lung problems.

Your GI provider with the help of a dietician/nutritionist will assess your child’s condition and determine appropriate treatment. A full evaluation may include laboratory studies, food diaries to assess caloric intake, and possibly endoscopic studies. The treatment will comprise of dietary modifications and supplementation, and management of underlying causes for the FTT.

- Hepatitis A: Hepatitis A is caused by a virus and is typically caught by close contact with an infected person or by ingesting contaminated food or water. Over 25,000 cases per year are reported in the United States.

- Hepatitis B: Hepatitis B is caused by a virus spread through contact with blood or bodily fluids of an infected person. This includes mother-to-child transmission. Approximately 43,000 people per year are infected in the United States and 1.25 million people in the US are chronically infected with hepatitis B. Some people recover completely while for others it becomes a chronic infection.

- Hepatitis C: Hepatitis C is a contagious liver disease that ranges in severity from a mild illness lasting a few weeks to a serious, lifelong illness that attacks the liver. It results from infection with the Hepatitis C virus (HCV), which is spread primarily through contact with the blood of an infected person.

- Autoimmune hepatitis: Autoimmune hepatitis is a condition in which a person's own immune system attacks the liver, causing swelling and liver cell death. The swelling continues and gets worse over time. If not treated, this can lead to permanent cirrhosis (a disease of the liver caused by liver cells that do not work properly), and eventually liver failure. Symptoms of autoimmune hepatitis may include enlarged liver, itching, skin rashes, dark urine, nausea, vomiting, pale or gray colored stools, loss of appetite. When autoimmune hepatitis progresses to severe cirrhosis, other symptoms such as jaundice (yellow coloring to the skin and eyes), swelling of the belly caused by fluid, bleeding in the intestines, or mental confusion can occur. A routine blood test for liver enzymes can show a pattern typical of hepatitis, but more tests are needed to make a diagnosis. Certain blood tests that look for antibodies (proteins that fight off bacteria and viruses) will be higher in someone with autoimmune hepatitis. A liver biopsy is needed to determine how much swelling and scarring has developed. The outlook for children with autoimmune hepatitis is generally favorable. In about seven out of 10 people, the disease goes into remission, with symptoms becoming less severe within two years of starting treatment. However, some people whose disease goes into remission will see it return within three years, so treatment may be necessary on and off for years, if not for life.

Other types of hepatitis include:

- Drug-related hepatitis

- Metabolic hepatitis (such as Wilson's Disease)

- Neonatal hepatitis

- Steatohepatitis (fatty liver)

- TPN-related hepatitis

Hirschsprung disease affects the large intestine (colon). Stool is normally pushed through the colon by muscles. These muscles are controlled by special nerve cells called ganglion cells.

Children with Hirschsprung disease are born without ganglion cells in the colon. In most cases, only the rectum is affected, but in some cases more of the colon, and even the entire colon, may be affected. Without these ganglion cells, the muscles in that part of the colon cannot push the stool out, which then builds up causing constipation and difficulty passing stool. Most babies with Hirschsprung disease do not pass stool on the first or second day of life. These infants may vomit and their tummy enlarge because they cannot pass stool easily. Some babies have diarrhea instead of constipation. Children and teenagers with Hirschsprung disease

usually experience constipation their entire life. Normal growth and development may be delayed. Your GI provider may order tests to diagnose Hirschsprung disease such as a barium enema, anorectal manometry, or rectal suction biopsy. The treatment for Hirschsprung is surgery to remove the affected parts of the colon.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

There are two primary types of Inflammatory Bowel Disease or IBD:

- Ulcerative colitis: Ulcerative colitis affects only the lining of the large intestine (the colon).

- Crohn disease: Crohn disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Most often Crohn’s disease affects the small or large intestines. It can cause inflammation in the lining and deeper layers of the intestines.

It is often difficult to diagnose which form of IBD a patient is suffering from because both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis cause similar symptoms. These children can have diarrhea, rectal bleeding, urgency with bowel movements, abdominal pain, sensation of incomplete evacuation, constipation. In addition, they may also have fever, loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, night sweats, joint pains and body aches.

Both illnesses do have one strong feature in common. They are marked by an abnormal response by the body’s immune system. The immune system is composed of various cells and proteins. Normally, these protect the body from infection. In children with IBD, however, the immune system reacts inappropriately causing harm to their gastrointestinal tract producing the symptoms of IBD.

Poor nutrition can lead to a variety of problems in children, including excessive weight gain and obesity. Childhood obesity can in turn be a precursor to many health problems, from Type II diabetes to heart disease to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). It is essential to provide your child proper nutrition and help him or her establish good eating habits that will last an entire lifetime. Kids are still growing and need lots of good nutrition to build strong bodies that will last their whole lives, but they don’t need empty calories found in junk food, soda and fatty

The pancreas is an organ in the middle of the upper abdomen, close to the first part of the small intestine, the duodenum. It produces specialized proteins called enzymes that are important in the digestion of proteins, fats, and sugars. The pancreas also produces insulin and other hormones important in maintaining normal blood sugar levels. Pancreatitis is an inflammation, or swelling, of the pancreas. Causes of pancreatitis include gallstones and toxins such as excessive alcohol. In children, common causes include viruses and other infections, medications, congenital malformations and other inherited conditions, and trauma to the

abdomen. In 1 out of 4 childhood cases, a cause is never found. Inflammation of the pancreas is often associated with pain in the upper abdomen and/or the back which may develop slowly, be mild and of short duration, or be sudden in onset, more severe and longer lasting. Nausea and vomiting are very common, fever and jaundice may be present. When pancreatitis is suspected, laboratory tests search for higher than normal levels of some of the proteins produced by the pancreas, such as “amylase” and “lipase”. An abdominal ultrasound (sonogram) or a CAT scan (computer tomography) of the abdomen can help show the inflammation and swelling of the pancreas and surrounding tissues. Once pancreatitis is diagnosed, other blood tests are done to search for a cause and to look for any complications due to the inflammation. Repeated inflammation of the pancreas is rare, but when it occurs it may lead to chronic problems with digestion, diabetes, and recurrent or persistent pain.

Reflux & GERD

In babies it’s called spitting up. In older kids, the signs of reflux and GERD can be burping, stomach aches, and heartburn. Most people experience acid reflux sometimes, and it’s usually not a problem. Even infants who spit up frequently are usually perfectly healthy.

However, in some people, reflux happens so frequently and is so severe that it develops into a condition called gastro esophageal reflux disease (GERD). GERD occurs when reflux causes troublesome symptoms or complications such as failure to gain weight, bleeding, respiratory problems or esophagitis.

In many cases GERD in kids can be managed with lifestyle changes, and without medication.

Treatments

Pneumatic dilation (PD) is considered to be the first line nonsurgical therapy for achalasia. The principle of the procedure is to weaken the lower esophageal sphincter by tearing its muscle fibers by generating radial force. The endoscope-guided procedure is done without fluoroscopic control. Clinicians usually use a low-compliance balloon such as Rigiflex dilator to perform endoscope-guided PD for the treatment of esophageal achalasia. It has the advantage of determining mucosal injury during the dilation process, so that a repeat endoscopy is not needed to assess the mucosal tearing. Previous studies have shown that endoscope-guided PD is an efficient and safe nonsurgical therapy with results that compare well with other treatment modalities. Although the results may be promising, long-term follow-up is required in the near future.

Anorectal manometry is used to test for the normal relaxation of the muscles which help to control bowel movements. These muscles are known as sphincters. Normally these muscles are closed to keep stool in the rectum and open when it is time to have a bowel movement. Anorectal manometry can also test for how the child senses distention or stretching of the rectum. A tube with a balloon on its end is inserted into the rectum. The balloon is slowly inflated to simulate stool in the rectum. As the balloon is inflated the muscles should open. The tube is connected to a computer which will measure how well this happens.

Hydrogen breath testing is used to evaluate several different gastrointestinal problems including intolerance of various sugars (such as lactose intolerance) and overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine. Bacteria in the intestinal tract can produce hydrogen when they are exposed to unabsorbed sugars. This hydrogen gets into the bloodstream, is taken to the lungs, and then removed from the body in the breath. To do this test, the child is asked to blow into a bag (to get a baseline reading). Then they are given a measured amount of a specific sugar to drink. At intervals after this, the child blows into a bag. The hydrogen in their breath will be measured. The test takes about 4 hours.

A colonoscopy is a test that allows the doctor to look directly at the lining of the large intestine (colon) using a long flexible tube that has a light and video chip at the end (colonoscope). Prior to this test the child must take medication that will clean stool out of the colon. The colonoscopy is done while the child is asleep under anesthesia. The colonoscope is passed up through the anus, into the rectum and then around the remainder of the colon. Frequently, tiny samples of cells (biopsies) are taken to look for inflammation, infection, or other problems.

Endoscopic treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding

There are a variety of endoscopic treatment modalities available for the management of UGIB, including injection methods, mechanical therapy, and cautery. The primary mechanism of action of injection therapy is tamponade (closure or blockage of the bleeding) resulting from volume effect. Some agents also have a secondary pharmacologic effect. Agents available for injection to produce tamponade include normal saline solution and dilute epinephrine. A separate class of injectable agents includes thrombin, fibrin, and cyanoacrylate glues, which are usedto create a primary tissue seal at a bleeding site. Mechanical therapy refers to the use of a device that causes physical blockage or closure of a bleeding site. Currently, the only endoscopic mechanical therapies widely available are clips and band ligation devices. Endoscopic clips are deployed over a bleeding site (eg, visible vessel) and typically slough off within days to weeks after placement. Cautery refers to the use of mechanical pressure of the probe tip on the bleeding site combined with heat or electrical current to coagulate blood vessels.

Sometimes a child or adolescent can develop a stricture (narrowing) in the esophagus (swallowing tube) that requires dilatation (stretching) to allow for easy passage of food and liquids. There are several ways of dilating the esophagus. One method is to use a series of flexible dilators of increasing thickness called bougies. These are passed down through the esophagus one at a time starting with a thin bougie that can pass through the narrowed area; as the size of the bougie increases, it stretches the strictured area. A second method is using a balloon dilator. Under x-ray guidance, a catheter with a balloon is placed through the area of narrowing; the balloon is then inflated which stretches the stricture.

Esophageal manometry is used to study how the esophagus (swallowing tube) is working. The child is awake for this test. A small tube (catheter) is passed through the nose and into the esophagus. The child is then asked to swallow both with and without sips of water to drink. The catheter is attached to a computer that records the strength and coordination of muscle contractions in the esophagus that occur with these swallows. The catheter needs to be moved during the study to test different areas of the esophagus.

Varices are large, dilated veins that develop in the esophagus (swallowing tube) when there is elevated pressure in the portal vein, the large vein that enters the liver. This elevated pressure can occur under several circumstances including severe liver disease and thrombosis (clotting) of the portal vein. Sometimes these varices can bleed or be at high risk of bleeding. One way to control this is to put a “band” on the vein so that it clots and then will not bleed. The bands are placed using an endoscope. This is done while your child is asleep under anesthesia. A fiberoptic tube (endoscope) is passed through the mouth and into the esophagus. There is a light and video chip on the end of the endoscope that sends images to a screen. A special device, called a bander, is attached to the tip of the endoscope. Once a varix is identified, a band can be placed around the vein. Bands can be placed on several different varices at the same session. It often requires several sessions, each scheduled several weeks apart, to take care of all the varices.

Esophageal varices sclerotherapy

Varices are large, dilated veins that develop in the esophagus when there is elevated pressure in the portal vein, the large vein that enters the liver. This elevated pressure can occur under several circumstances including severe liver disease and thrombosis (clotting) of the portal vein. Sometimes these varices can bleed or be at high risk of bleeding. These can be controlled either by banding (see above) or sclerosing the varices. Sclerotherapy is performed by injecting a medication into the varix that causes it to scar. If the varix is scarred, it cannot bleed. This is done while your child is asleep under anesthesia. A fiber optic tube (endoscope) is passed through the mouth and into the esophagus. A sclerotherapy needle is passed through the endoscope. Once a varix is identified, the needle is advanced into the vein and the medication injected. Several different varices can be injected at the same session. It often requires several sessions, each scheduled several weeks apart, to take care of all the varices.

A flex sigmoidoscopy is a test that allows the doctor to look directly at the lining of the lower end of the large intestine (rectum and sigmoid colon) using a flexible tube that has a light and video chip at the end (either a sigmoidoscope or a colonoscope). Prior to this test the child must take medications that will clean stool out of the colon. The scope is passed through the anus, into the rectum and then into the sigmoid colon. Frequently, tiny samples of cells (biopsies) are taken to look for inflammation, infection, or other problems.

A child or adolescent may swallow a coin, toy, large piece of food that is not chewed well, or other object. If this gets stuck in the esophagus, it must be taken out. To do this, an endoscope (fiber optic tube) is passed through the mouth and into the esophagus. Various tools (graspers and baskets) are available that can be passed through the endoscope and then used to grab the object and pull it out of the esophagus. If the object gets through the esophagus and into the stomach, with time it will usually pass through the rest of the intestinal tract and come out in the stool. For this reason, foreign bodies in the stomach only need to be removed by endoscopy if they are causing symptoms (such as abdominal pain or vomiting) or if the object has remained in the stomach for a prolonged time.

A number of tests are available to see how well the pancreas is making the enzymes that break down food. These include simple stool tests. Sometimes it is important to measure the amount of the enzymes that gets into the small intestine. This is done at the time of an upper endoscopy. After the child is asleep, under anesthesia, they are given a medication through an IV that stimulates the pancreas. This causes fluid from the pancreas to empty out into the first part of the small intestine (duodenum). This fluid is suctioned out through the endoscope and collected in a container. It is then sent to a laboratory where the amount of enzymes in the fluid is measured.

Some children need a tube placed in their stomach (gastrostomy tube) to allow them to get adequate nutrition if they cannot take in enough by mouth or to allow them to take in liquids safely if they have a swallowing problem. There are several ways that these tubes can be placed. One is a Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG). With the child either asleep under anesthesia or with IV sedation, the endoscope (fiber optic tube) is passed through the esophagus and into the stomach. The stomach is then inflated with air through the endoscope. After carefully cleaning the abdomen, a place for the gastrostomy tube is identified, and at this spot a small needle is passed through the abdominal wall and into the stomach. A flexible wire is then passed through this needle and the needle is taken out. The flexible wire is grabbed using the endoscope and pulled out through the mouth. The gastrostomy tube is then attached to this flexible wire and pulled down the esophagus and then out the small opening that was made in the abdominal wall at the site of the needle puncture, leaving the bumper of the gastrostomy tube in the stomach, holding the tube in place. The entire procedure, after the child is asleep, takes only 5-10 minutes. The child will stay in the hospital overnight and usually the tube will be used for feedings the next day. The family is taught how to use and care for the tube before going home.

These tests are used to measure how often material refluxes from the stomach back into the esophagus (gastroesophageal reflux). The pH probe measures acid reflux. The impedance catheter measures both acid and nonacid reflux. Your child’s doctor will decide which test will be most helpful. For both tests, a small, flexible catheter is passed through the nose and into the esophagus. The catheter is attached to a recording device. The catheter is left in place for 24 hours. During this time your child can eat and drink normally.

Polyps are relatively common in children. Many of these are juvenile polyps which are not cancerous. Some polyps occur as part of a polyposis syndrome. As part of both the evaluation and treatment of polyps, they are removed endoscopically by polypectomy. This is done through the colonoscope if the polyps are in the colon (large intestine) which is the most common location, or through the endoscope if the polyps are in the stomach or small intestine. If the polyp is very small, it may be removed with a biopsy forcep which is passed through the endoscope or colonoscope. If the polyp is larger, the base of the polyp is grabbed by a snare which is passed through the endoscope or colonoscope. This allows the polyp to be taken off. Whether removed by biopsy forceps or snare, the polyp is sent to pathology to be examined under a microscope to determine what type of polyp it is.

Pyloric dilation (including Botox injection)

For patients with an impaired ability to push food from the stomach into the small intestine, endoscopic treatment of the valve (pylorus) connecting these two organs may offer relief. These patients are typically diagnosed with “delayed gastric emptying” or “gastroparesis” and often have chronic symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and/or weight loss. This condition may occur in an otherwise healthy child following a viral illness, or it may be part of an underlying genetic or metabolic disorder. Regardless of the cause, patients who have had unsuccessful treatments with medications may be considered for endoscopic therapy. By dilating or stretching open the pyloric valve and/or injecting botox to force the valve to relax, the stomach may have an easier time emptying into the small bowel and improve symptoms.

Rectal dilation (including Botox injection)

Botox® is the brand name of a toxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum (botulinum toxin). When a small amount is injected into a muscle, it causes the muscle to relax. Your child’s doctor may recommend Botox® injection of the anal sphincter under selected circumstances, such as when the child is having difficulty with stooling specifically because of problems with relaxation of the muscles that make up the anal sphincter. The injection is done while the child is asleep under anesthesia. The effect on the muscle is not permanent but can last for many weeks to months.

A rectal biopsy is a procedure to remove a small piece of rectal tissue for examination. The sample is sent to the laboratory for analysis.

This advanced diagnostic procedure offers the ability to visualize the middle of the small intestine, an area not accessible with traditional upper or lower endoscopies. With the use of a longer, more flexible endoscope, coupled with a specialized overtube with a balloon at the end, the endoscopist is able to “inchworm” their way through the small intestine by repeated inflations and deflations of the balloon. If lesions are identified, they can then be removed, marked for surgeons to potentially remove at a later time or treated to stop bleeding.

Upper endoscopy or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

An upper endoscopy or EGD is a test that allows your child’s doctor to examine the lining of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (first part of the small intestine). It is done while the child is asleep under anesthesia or is sedated. A fiber optic tube (endoscope) is passed through the mouth, down the esophagus and into the stomach and then the small intestine. There is a light and video chip on the end of the endoscope that sends images to a screen. Frequently, tiny samples of cells (biopsies) are taken from the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum to look for inflammation, infection, or other problems.

Noninvasive capsule endoscopy (sometimes called “pill cam”) allows for visualization of the lining of the small intestine in areas of the intestine which cannot be seen with standard endoscopy. This can be helpful in the evaluation of a number of problems, such as identifying a source of bleeding in the small intestine, further evaluation of inflammatory bowel disease, or looking for polyps or other lesions in the small intestine. The capsule is about the size of a large vitamin pill and contains a light and video chip that sends images to a computer. Many can swallow the capsule. For those who cannot, the capsule can be placed in the small intestine using endoscopy; in this case, the child is asleep under anesthesia when the capsule is placed. The capsule travels through the intestinal tract taking pictures for eight hours. These pictures are captured by a receiver that the child wears on a belt. The capsule will ultimately be passed harmlessly in the stool and is discarded. Pictures are downloaded from the receiver and then reviewed by the doctor.